Gordon Willis was named by Conrad Hall “the Prince of Darkness.” Well, here is a dark, contrasty, moody shot of a nothing subway train. Nothing until you account New York’s subway system handles 6 million people day. That is not nothing. So this shot, as well as showing a Willis propensity for darkness, I think also is a good example of “dark against light and light against dark” as Connie might have seen.

Recently, a few friends have stated that my career in cinematography is evident in my railroad shots. I must admit I had to think about that for a bit.

My career in the movies was mostly as a Camera Assistant, not the head of the department Director of Photography. My job required me to assemble the camera as per the head DoP’s instructions and during the actual take, keeping the actor in focus. As such, I was witness to thousands of sets where the lighting and camera was arranged just so for the finest emotional effect to advance the story.

In train photography, there are two camps: the conservative, fully-lit document of the train and the liberal interpretive image that just uses the train as a starting point for an artistic statement. Interestingly, this dichotomy has been existence throughout the history of Western art, a pendulum as it were where the style would go from conservative to liberal.

This phenomenon is also known in movie business cinematography. In the 1920’s, cameramen like William Daniels shooting Greta Garbo, or Karl Strauss lensing “Sunrise” were breaking down all barriers and creating astonishing cinematography.

Willis, a confirmed New Yorker, didn’t play the Hollywood game with whom he called the “Old Guard cameramen who wore white shoes.”

By the 1970’s however, Hollywood had gotten very conservative. It took breakout work like Director of Photography Gordon Willis’s on “The Godfather” to break that up. “Godfather I & II” are arguably the greatest examples of cinematography of the decade but Willis, a confirmed New Yorker, didn’t play the Hollywood game with whom he called the “Old Guard cameramen who wore white shoes.” These conservative fellows proclaimed Willis’s work appalling because, with the backlighting he employed, the audience couldn’t always see the eyes of the main actor Marlon Brando. Little did they care that it was Gordon’s point that Vito Corleone thoughts were hidden. In reality, I think deep down those men were jealous because they knew if they had tried the same thing, they would have gotten fired by their equally stodgy producers. In any event, Gordon’s greatest work was ignored by the Oscars.

In movies, it is part of the process that every tool is used to convey the story. You do this with the script, the acting, the cinematography, the sound, the music, the editing. With the camera, there are tools within it. First the lens selection then the type, color and placement of the light. Gordon was very specific in this process. He would talk about reducing the variables to the point the final choice became self evident.

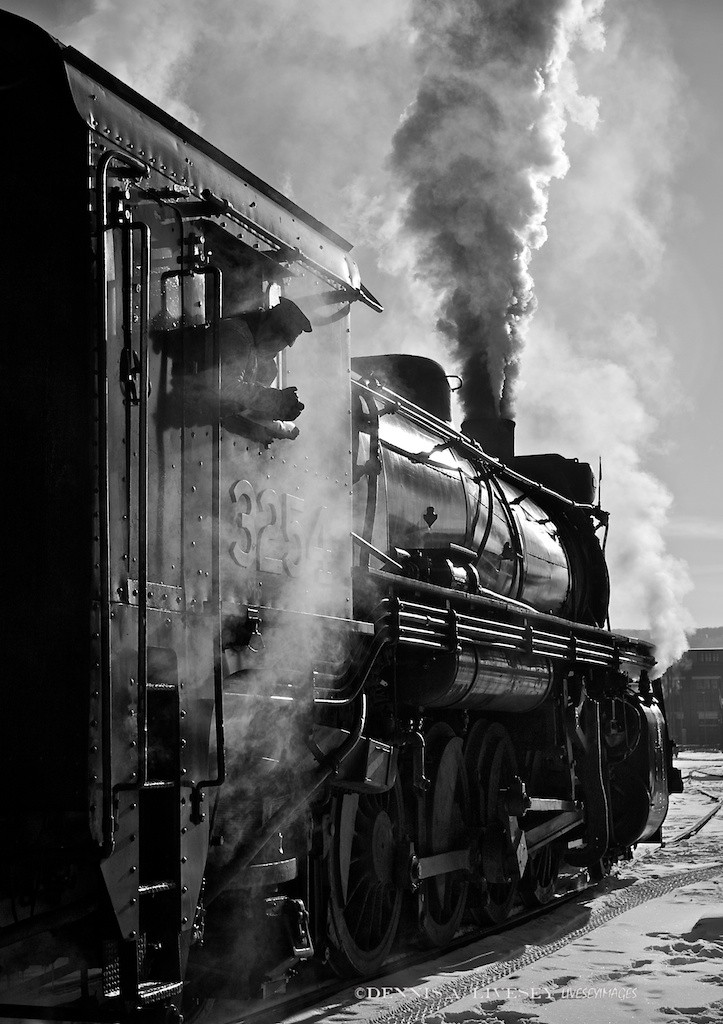

On January 17th, 2009, I took this image of Steamtown’s CN No. 3254. The temp was around 10F, fairly new snow was on the ground and, most astonishingly, the sky was clear. Being winter, the sun was low and with the clear sky and snow, the light was utterly amazing for Scranton! I kept finding these exciting shots looking into the sun. The front lit was good, don’t get me wrong, but the back lit stuff had my fun meter pinned. I think Gordon Willis would approve for not only can’t you see engineer Aaron Stout’s eyes, you can’t see his face! The light, the steam, the vapor, the black engine and the white snow are so contrasty, I even like to think Conrad Hall would smile.

Ultimately, the task was to pick the absolutely correct tool for that movie, that scene, that shot. He felt there was only one choice that would be appropriate. In every movie he shot his perfect cinematography backs up this statement totally.

A great compatriot of Willis was Conrad Hall. Connie, as he was affectionally known, won the Oscar for “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” “American Beauty” and “Road To Perdition.” He was nominated a total of 10 times. (Apparently he knew the right thing to say to the guys in the “white shoes.”)

If you watch any of Connie’s films, the beauty of his lighting is unbelievable. You will see light, often backlight, used to convey beauty, happiness, fear, tragedy. One of his crew told me that Connie would say “Think of every shot you ever felt was outstandingly beautiful. Look at it and try to tell why. In time you will see the answer. You will see that it is the interplay of light against dark and dark against light.”

I feel he was saying that it is contrast (and high contrast backlighting at that) which becomes such candy your eye cannot resist.

When I became active in the digital age and started uploading to railroad photography forums and websites, I recall scratching my head with one site’s prohibition about uploading any shot that was “backlit.” What? In movies we always used that for drama. What are trains if not dramatic? It took an epiphany for me, (that’s another story) which occurred on January 17th, 2009 to start figuring out how to apply cinema backlighting to the train pictures I do.

As one who wants to impart emotion in his work, I do find I use the thoughts of these great artists. I do try to get the perfect tool for the shot and I do try to find that contrasty, beautiful light to convey the excitement these things on flanged wheels create in so many people.

More of Dennis’ photography can be viewed from these links.

Website | Flickr | Railpictures

About the Author

Dennis A. Livesey, a confirmed New Yorker, has been taking pictures since he was four years of age. Owning a camera since then, he has made his living in the photographic industry for his entire adult life. Coincident with the interest in photography was the growth of his interest in railroads. In neither case can he explain the attraction. At this juncture the best he can articulate is that it is a fascination with machines, both big and small, and the inexpressible, underlying emotion these two avocations can generate. With the change from a cinematography career to a much less demanding retail position, his rail photography efforts have greatly expanded. With that has come a very different level of participation in the hobby that has been most gratifying. Simply put, it’s been a hoot and there is no end in sight!

Like and Share with your friends and family!